All of Me Digital Lobby Display

It’s your classic romantic comedy.

Boy meets girl. Boy uses a wheelchair. Girl uses a scooter.

They both use AAC to connect with the world around them.

Boy meets girl. Boy uses a wheelchair. Girl uses a scooter.

They both use AAC to connect with the world around them.

AAC stands for alternative and augmentative communication: in very broad terms, this means any way that a person communicates that is not spoken language. Although things like sign languages, writing, and drawing technically qualify as AAC, usually it’s used to refer to communication that’s aided with a tool or device. The most common forms of AAC today are analog communication boards, which might be anything from a single page to an expansive binder, and apps that can be used on tablets, phones, or Internet browsers, which often use a digitized voice to read out whatever the user has put in. AAC often has both symbols and text, which increases accessibility.

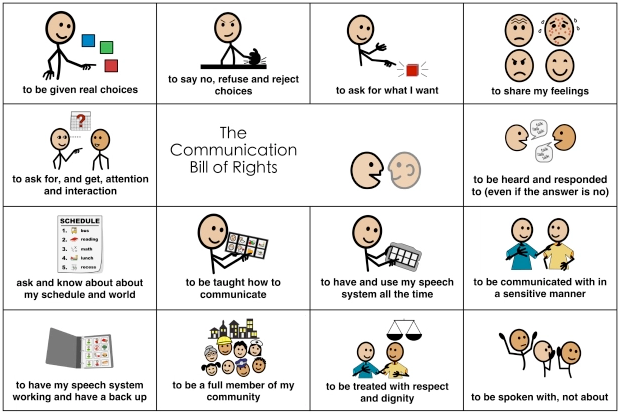

It is really, really important to recognize that AAC users are often ignored, left out of conversations, or treated like they are much less capable because they don’t communicate via spoken language, and it is even more important to recognize that this is wrong. All people have a fundamental right to communicate their wants, needs, thoughts, and opinions in whatever format is accessible to them, which means that all people also have the responsibility to treat different forms of communication as equally valid. This Communication Partner Profile from OpenAAC asks people to consider how they interact with AAC users and how they might improve their conversational skills.

Below is a very broad timeline of some AAC developments. It’s very important to recognize that the first commercially reproduced AAC method is not the first AAC use. As long as there have been nonspeaking disabled people, there have been efforts to communicate with them. Whether those efforts are from the disabled person themself, their caregivers, friends, or family, they did exist.

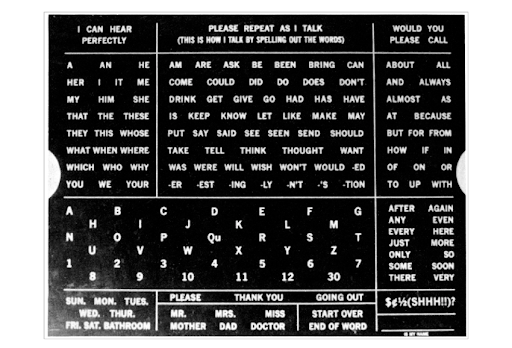

The F. Hall Roe’s communication board consisted of letters and words printed on Masonite, and it was the first widely available communication aid.

The Tufts Interactor Communicator (TIC) used scanning to provide access to display and printers and later introduced changing the scanning letter arrangement dynamically based on the probability of the next letter to be selected while typing.

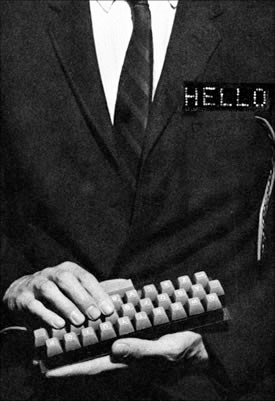

“The Talking Brooch,” a wearable communication aid, was designed for individuals who could not talk but could type on a keyboard held in the hand.

Sentient Systems Technology, Inc. (today Tobii DynaVox) is founded. This was the first company to release a speech-generating device with a touchscreen, 1991’s DynaVox.

All of Me becomes the first show Off-Broadway to feature two characters using AAC to speak to each other on stage.

The two main characters in All of Me, Lucy and Alfonso, both use text-to-speech AAC. In the world of the show, they have iPads where they type into one of the many AAC apps that exist. Once they’re ready to say their thought, they hit a button that reads it in a digitized voice. Their devices would have some kind of external speaker to make them louder than the average iPad is capable of. Alfonso, whose family is well-off, has a digitized voice that sounds more like a human speaking voice. Lucy, whose family is not, has a default voice that sounds more robotic.

AAC is becoming more and more accessible for a lot of reasons, including how commonplace internet-enabled devices are, the number of AAC apps and methods available, and the awareness of its existence by both the medical and disability communities. An outdated standard recommended that AAC only be introduced if a child went through speech therapy and was not able to learn clear and effective spoken language, which meant that many disabled children were not able to communicate easily for years and years. Today, AAC may be introduced formally or informally to children of all ages without regard for their spoken language abilities.

Many AAC apps use a symbol-and-text combination of buttons that are color-coded into categories. For example, in the Fitzgerald color system, verbs are on green buttons; nouns are on orange; important words or negative words are on red; and so on and so forth. This lets experienced users find buttons more quickly and can help with introducing new vocabulary to young children. One common way of organizing the buttons is a core and periphery model; imagine if every time you wanted to pick a word, you had to find it in a picture of every word you know! The core board avoids this by having the most commonly used words on the ‘home’ page with buttons that serve as shortcuts to more pages.

Most regular AAC users have very customized systems; the words that are most important to one person might not be in another person’s vocabulary at all. The pathways to get to different pages and sets of words can also be customized to match the user’s thought processes and associations. Most systems have built-in dictionaries of symbols and words, but users can also create custom buttons with their own labels and photos. Just like how non-AAC users develop their own personal dictionaries through the process of learning, growing, and having interests in different subjects at different times, so do AAC users! The difference is, their personal dictionaries exist in places other than their brains.

Try some web-based AAC apps on your mobile device. Additional apps are also available in the app store, and there are dozens of other AAC apps that range in price from free to hundreds of dollars.

Apps:

CoughDrop Quick Core 60 sample board

Challenge #1: Try to say the following sentences on each app.

Where is the bathroom?

Don’t touch me.

My favorite show is All of Me, what’s yours?

How many buttons did you need to press? How long did it take you to find each one? Did the AAC voice sound like you?

Challenge #2: Below is a graphic version of the Communication Bill of Rights. Think about the AAC apps you trialed. How well could you do each of the things on this list?

https://www.openaac.org/index.html

https://www.assistiveware.com/blog/how-to-talk-about-aac

https://www.openaac.org/index.htmlhttps://www.assistiveware.com/blog/how-to-talk-about-aac

https://grid.asterics.eu/#about

Lobby Display materials by Caitlin Cafiero, All of Me Production Accessibility Coordinator